Back at Phu Bai, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest C. Cheatham reviewed Marine Corps urban combat doctrine, which recommended staying off the streets and moving forward by blasting through walls and buildings. Accordingly, he continued to gather the necessary equipment he would need to accomplish his mission, including M20 Rocket Launchers, M40 106mm Recoilless Rifles (mounted on flatbed vehicles called “mules”), C-4 explosives, flamethrowers, tear gas, and gas masks.

Cheatham received this equipment early in the afternoon of February 3. After a council of war, Cheatham deployed his battalion to recapture the southern section of Huế. Many Marines serving under Task Force X-Ray had no previous combat experience in urban warfare/close-quarters combat. Because of the cultural and religious significance of Huế City, Allied forces were ordered not to bomb or shell the city. In any case, seasonal monsoons prevented allied forces from employing air support. However, as the intensity of the battle increased, the “no bombing” restriction was lifted.

The NVA’s tactics were to remain as close to the Marines as possible, which enemy planners imagined would negate the effective use of artillery and close air support. The NVA maintained a forward fighting line directly opposite the Marine’s positions, with a secondary line only two blocks to the rear. Snipers and machine guns intensely defended each building within the battle zone.

The enemy also prepared spider holes (fox holes) in gardens and streets to create crossed fires between all buildings and streets. If the Marines penetrated the forward line, the NVA would withdraw to the secondary line, and the business would begin anew. At dusk, the NVA and VC would attempt to reinfiltrate their former positions.

On the night of February 3, the NVA commander, seeing the buildup of Marines at Huế University, thinned out his frontline forces, leaving just a platoon to defend the Treasury building and adjacent Post Office. Then, on the morning of February 4, when the Marines launched their attack on the Treasury building, murderous enemy crossfires penned the Marines down for hours.

The only way to break out of their stalemate was to blow a hole into the side of buildings and clear it, room by room. These actions were costly to the Marines performing such missions, but they were also costly to the overall operation because the process was time-consuming. Under cover of tear gas and the residue of overwhelming M48 and M40 fires, Marines were able to cross city streets to employ plastique explosives and rocket launchers.

Slowly but steadily, Marines pushed into the Treasury building, post office, and the Jeanne d’Arc High School, killing the enemy in massive numbers. Marines also suffered the fate of combat. Company A 1/1 lost half of his men (wounded and killed) in a single day’s fighting. In addition to locating the enemy and destroying them, Marines also rescued and protected Vietnamese civilians trapped by the NVA and VC assault. That evening, VC sappers succeeded in blowing up the An Cuu bridge, cutting the road link to Phu Bai.

Following the capture of the Treasury, Cheatham continued his methodical advance to the west, leading with tear gas, M48s, and Ontos—followed by Mules and Marine grunts. As NVA-VC’s manpower and ammunition were depleted, resistance lessened. The enemy no longer tenaciously defended each building; they relied more on sniper fire, mortars, and rockets.

On February 5, Marines recaptured the Huế Central Hospital complex, rescuing Lieutenant Colonel Pham Van Khoa (the Mayor of Huế and Thua Thien Province chief), hiding in the grounds. The next day, Marines attacked the Provincial Headquarters, which served as the command post of the NVA 4th Regiment. While the Marines were seizing the surrounding walls, the area between the wall and buildings was covered by fire from every enemy-held window and spider-hole inside the grounds.

Marines sent an Ontos forward to blast an entry into the building, but the enemy disabled it with a B-40 rocket. Next, the Marines sent a Mule forward to blow a hole in the building, which allowed the Marines to advance under cover of tear gas. Once they entered the building, Marines fought room by room to clear out the enemy — but many of the NVA slipped away. After securing the building, Marines cleared the spider-holes, giving no quarter to their occupants.

To celebrate their victory, Marines raised an American flag, but they were ordered to lower it because Vietnamese law prohibited the flying of any foreign flag unless the flag of the Republic of Vietnam accompanied it.

After resting his men at the Provincial Headquarters, Cheatham advanced west toward the Phu Cam Canal. He swung south and east to clear the area with the canal to his right. On February 7, the NVA twice ambushed a 25-vehicle supply convoy on Route 547 from Phu Bai to the 11th Marines firebase Rocket Crusher. The 11th Marines provided artillery support to Allied forces fighting in and around Huế.

Enemy ambuscades killed twenty Marines and wounded thirty-nine. NVA sappers finally succeeded in destroying the Trường Tiền bridge, which restricted all movement between the old and new cities. NVA forces in the new town, worn down by more than a week of constant combat and effectively cut off from their comrades on the other side of the river, began to abandon the city slowly. The 815th and 2nd Sapper Battalions moved to the southern side of the Phu Cam Canal, joining the 818th Battalion. The 804th Battalion and the 1st Sapper Battalion remained south of the canal near the An Cuu Bridge. At the same time, the 810th Battalion began preparing to sneak west across the Perfume River by raft and boat to Gia Hoi Island.

Colonel Gravel’s 1/1 had been engaged in clearing operations to the east and south of the MACV compound. On February 10, they captured the soccer stadium, giving the Marines a second (and much safer) helicopter landing zone. Combat engineers built a pontoon bridge across the Phu Cam Canal, restoring the road access that had been lost when the An Cuu Bridge was blown up.

On February 11, Hotel Company 2/5 secured a bridge over the Phu Cam Canal and the city block on the other side of the canal. The next day, Fox Company swept the west bank of the canal, fighting through houses and the Huế Railway Station that had been sheltering NVA snipers. On February 13, Fox and Hotel companies crossed the bridge again to secure the entire area. As Marines advanced into the open countryside towards the Từ Đàm Pagoda, they located freshly dug NVA graves and then were hit by a barrage of mortar fire, forcing them to withdraw. Two-Five had inadvertently stumbled on the NVA’s field command post.

On February 13, General Creighton Abrams established his forward headquarters at Phu Bai, replacing General Cushman and assuming overall command of U.S. forces in CTZ I.

The Citadel

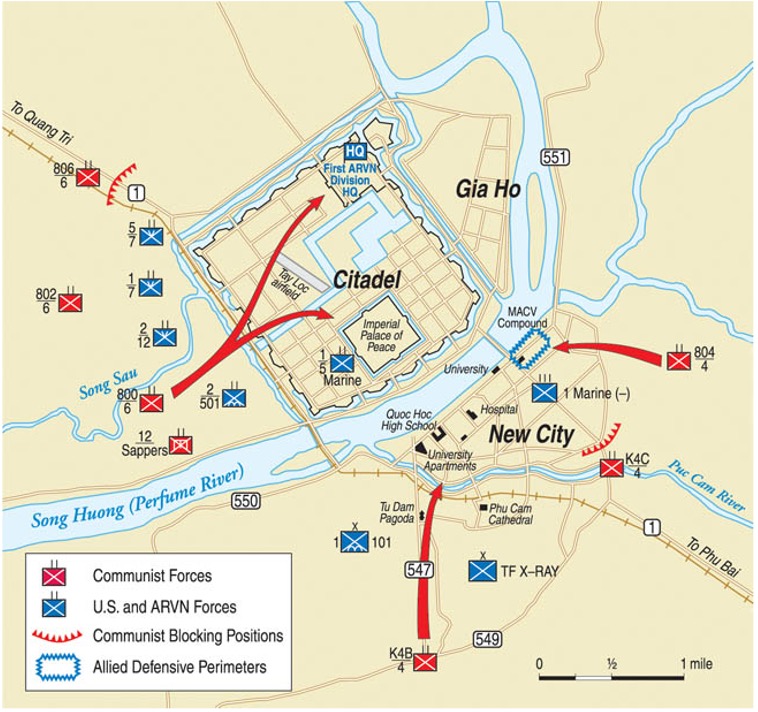

While the ARVN 1/3 and 2nd and 7th Airborne Battalions were busy clearing out the north and western parts of the Citadel, including the Chanh Tay Gate, the ARVN 4/2 moved south from Mang Ca toward the Imperial Palace. In those operations, South Vietnamese forces killed over 700 NVA-VC troops. On February 5, NVA-VC units managed to stall ARVN airborne units, prompting General Trưởng to replace them with his 4th battalion, 2nd Regiment (4/2). Meanwhile, the ARVN 4/3, operating south of the river, assaulted the Thuong Tu Gate near the eastern corner of the Citadel.

After seven successive attempts to breach the gate failed, 4/3 was ordered to reinforce the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 4th regiment. On 6 February, the ARVN 1/3 captured the An Hoa Gate and the northwest corner of the Citadel, and the 4th Battalion seized the southwest wall. That night, the NVA counterattacked with a battalion from the NVA 29th Regiment, scaling the southwest wall and pushing the 4th Battalion back to Tây Lộc.

On February 7, the ARVN 3rd Regiment, which had been futilely trying to break into the southeast corner of the Citadel, was moved by LCM-8s (Mike Boats) to Mang Ca to reinforce units inside the Citadel. The ARVN 2nd Troop, 7th Cavalry (equipped with fifteen M113s) arrived at Mang Ca from Quảng Trị to relieve the 3rd Troop. To avoid enemy ambushes, the 2nd Troop turned off Highway One a few miles north of the city, traveled east cross-country and swung around to the rear of Mang Ca through the Trai Gate.

Also, on 7 February, the North Vietnamese tried to bring their air support into the battle, sending four North Vietnamese Air Force (Il-14) transport aircraft from Hanoi. The Ilyushin IL-14 was a Soviet production of the Douglas DC-3. Two of the aircraft carrying explosives, antitank ammunition, and field telephone cables managed to find an opening in the cloud layer about six miles north of Huế. They dropped their cargo in a large lagoon for local forces to retrieve. One of the aircraft returned safely, but the other, flying through dense fog, crashed into a mountain, losing all on board.

Meanwhile, the other two Il−14s, modified to drop bombs, were ordered to bomb Mang Ca. However, neither aircraft could find the city in the fog, so they returned to their base with all their artillery. Five days later, they tried again, but bad weather prevented them from locating Mang Ca. The two aircraft radioed that they were scrubbing the mission and then headed to sea to jettison their bombs. A short time later, both aircraft disappeared while over water.

On February 10, two forward observers from the Marines’ 1st Field Artillery Group were flown into Tây Lộc to help coordinate artillery and naval gunfire to support the fighting inside the Citadel. However, General Ngô Quang Trưởng directed that the Marines should not target the Imperial Palace under any circumstances.

On February 11, The South Vietnamese Marines (Task Force Alfa) (the 1st and 5th Battalions) began to replace the Vietnamese Airborne units by helicopter, as Bravo Company 1/5 was airlifted to Mang Ca. Intense enemy fire precluded a full insertion, however. On February 13, Alpha and Charlie Companies 1/5, supported by five M-48s from the 1st Tank Battalion, were loaded into LCM-8s (Mike Boats) and ferried across to Mang Ca. Once there, the Marines moved south along the eastern wall of the Citadel while Bravo Company remained in reserve.

Unknown to the Marines, the ARVN Airborne withdrew from the area two days earlier when the Vietnamese Marines began arriving at Mang Ca. NVA defenders had used the opportunity of the delay to reoccupy several blocks of the Citadel and reinforce their defenses. Communist forces engaged Alpha Company, which almost immediately suffered 35 casualties. The CO of 1/5, Major Robert Thompson, ordered Bravo Company to relieve Alpha, and the advance continued slowly until NVA flanking fire halted it.

The next day, Marines resumed their attack, supported by Marine artillery, Naval gunfire, and Marine Corps close air support. Despite this, the Marines made little progress and had to withdraw. As soon as the Marines withdrew, the communists reoccupied those positions.

Delta Company arrived at the Citadel on the evening of February 14 after taking fire while crossing the Perfume River. On February 15, Delta Company led a renewed attack against the Dong Ba Gate, with Charlie Company defending its flank. After Bravo Company joined the assault, Marines secured the gate. The Marines suffered six deaths and fifty wounded, while the enemy sustained twenty deaths.

Also, on February 14, the South Vietnamese Marine Task Force joined the battle. The operational plan called for the VN Marines to move west from Tây Lộc and then turn south. However, they were soon halted by a strong NVA defense. After two days of fighting, the VN Marines had only advanced 400 meters. Meanwhile, the ARVN 3rd Regiment fought off an NVA counterattack in the northwest corner of the Citadel.

Despite their many setbacks, the communists appeared determined to prolong the battle. The 6th Battalion, 24th Regiment, 304th Division (originally located near Khe Sanh) reached the Citadel after following an intentionally convoluted route through Thon La Chu. The 7th Battalion, 90th Regiment, 324-B Divison was due to arrive within a few days — after a forced march from the DMZ.

On February 16, two companies from the 1st Battalion, U.S. 8th Cavalry Regiment, fought elements of the NVA 803rd Regiment, 324-B Division, about twelve miles northeast of Huế, killing 29 enemies before breaking contact the following day. Also, on February 16, 1/5 advanced 140 meters at the cost of seven Marines killed and 47 wounded. The Marines killed 63 of the enemy.

That same day, at a meeting at Phu Bai involving Generals Abrams, LaHue, Trưởng, and South Vietnamese Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, Kỳ approved the use of all necessary force to clear the NVA-VC forces from the Citadel, regardless of any damages to historic structures.

On the night of February 16, a radio intercept indicated that a battalion-size NVA force was about to launch a counterattack over the west wall of the Citadel. Artillery and naval gunfire was called in, and a later radio intercept indicated that a senior NVA officer had been killed in the barrage. Another intercept stated that the battalion commander requested permission to withdraw from the city, but his request was denied, and he was ordered to stand and fight.

Vietnamese forces resumed their attacks on February 17, and the Hac Bao Company was moved to support 1/5’s right flank. Over the next three days, these forces slowly reduced the NVA’s defensive perimeter.

On February 18, 1/8th Cav was attacked by elements of the 803rd Regiment twelve miles northeast of Huế. This second engagement convinced the NVA commander that the regiment could not reach the Citadel.

By February 20, the 1/5 advance had stalled. After conferring with senior commanders, Major Thompson launched a night attack against three NVA strongpoints, blocking further movement. At dawn, the entire battalion would assault NVA positions. At 0300 on February 21, three ten-man teams from the 2nd Platoon of Alpha Company launched their assault, quickly capturing the sparsely defended position the NVA had withdrawn from during the night.

As the NVA sought to reoccupy those positions the following day, they were caught in the open by the assaulting Marines from 1/5. Thompson lost three Marines in the fight, but 16 NVA were killed. At that moment, the Marines were only 100 meters from the south wall of the Citadel. That evening, Bravo Company was replaced by Lima Company, 3/5.

Unknown to either the Americans or South Vietnamese, the NVA had begun a phased withdrawal from the Citadel, making their way southwest to return to their bases in the western hills. Lima 3/5 was tasked with clearing the area through the Thuong Tu Gate to the Trường Tiền Bridge. They completed their mission, meeting little enemy resistance.

But to the west, South Vietnamese forces continued to meet stubborn resistance. On February 22, after a barrage of 122mm rockets, the NVA counterattacked Vietnamese Marines, who unmercifully pushed them back with the support of the Hac Bao Company.

Little progress was made on February 23, prompting a very frustrated General Abrams to suggest that the Vietnamese Marines should be disbanded. That night, the NVA attempted another counterattack but was forced back (again) by intense artillery. The ARVN 3rd Regiment launched a night attack along the southern wall of the Citadel. At 0500 the following day, they raised the South Vietnamese flag over the Citadel and secured the south wall by mid-morning.

General Trưởng then ordered the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Regiment, and the Hac Bao Company to recapture the Imperial Palace, which was achieved against minimal resistance by late afternoon. The last pocket of NVA at the southwest corner of the Citadel was eliminated in an attack by the 4th Vietnamese Marine Battalion in the early hours of February 25.

Mopping Up

On February 22, the ARVN 21st and 39th Ranger battalions boarded junks and traveled to Gia Hoi Island, where the communist provisional government had been headquartered since the offensive started. The Rangers swept the island as thousands of residents emerged from hiding and ran through their ranks to escape the battle. The most brutal fight of the day centered on a pagoda that contained an NVA battalion command post. The sweep continued through February 25. The three-day operation netted hundreds of VC cadre, many of whom were university students who, according to residents, had played a key role in rounding up government officials and intellectuals the NVA/VC targeted as threats to their new regime.

On February 23, a mechanized task force involving the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and Troop A, 3rd Squadron, 5th Cavalry swept along the northwestern wall toward the An Hoa Bridge, flushing out several NVA troops who had taken refuge in the thick grasses and weeds.

Meanwhile, a mile further to the northwest, the remainder of the 5/7th Cav resumed its advance toward Thon An. These troops fought their way into the NVA-occupied hamlet and found a honeycomb of tunnels and bunkers beneath its shattered remains. They spent the rest of the day searching the ruins for survivors. They also combed through the adjacent cemetery, where the 806th Battalion had ambushed the ARVN 7th Airborne Battalion on 31 January.

On February 24th, the 5/7th Cav rejoined its detached company and the armored cavalry platoon from the 3/5th Cavalry near the western corner of the Citadel. The combined force then swept toward the Bach Ho Railroad Bridge along the southwestern face of the Citadel, where a few NVA continued to hold out in a narrow band of trees.

While 1st Battalion, 1st Marines conducted clearing operations in southern Huế, 2/5 conducted security patrols south of the Phu Cam Canal. On February 24, 2/5 Marines launched an operation to the southwest of Huế to relieve the ARVN 101st Combat Engineers, which had been under siege by the NVA since the start of the battle.

As 2/5 approached the base at 0700, they were met by NVA mortar and machine-gun fire. Marine artillery pushed the enemy into a hasty withdrawal, and 2/5 entered the base at 0850. The base remained under fire from enemy positions in a Buddhist temple to the south and from a ridgeline to the west. At 0700 on February 25, Fox and Golf Companies 2/5 began their assault on the ridgeline. They were met by intense mortar fire. With support from Marine artillery, Marines secured part of the ridge, killing three communists.

The attack resumed the following morning. Hotel Company attacked a nearby hill, and after meeting stubborn resistance, the Marines pulled back so that air strikes could neutralize the enemy. Twenty enemy soldiers were killed, along with four Marines, from friendly fire. The Marines renewed their attack the following day, killing fourteen additional enemy.

On February 28, 1/5 and 2/5 Marines launched a combined operation to the east of Huế to try to cut off any NVA forces moving from Huế towards the coast. Only a few NVA were encountered and dealt with.

Operation Huế City officially concluded on March 2, 1968. ARVN losses included 452 killed and 2,123 wounded. American losses were 216 dead and 1,584 wounded. However, the numbers don’t add up. According to after-action reports, the NVA executed 4,856 captured civilians and ARVN personnel, but the official toll, as reported by the Vietnamese command authority, only 844 civilians were killed, with 1,900 (estimated) receiving combat injuries.

NVA/VC losses are also a matter of debate. North Vietnamese records indicate 2,400 killed and 3,000 wounded. General Abrams’ headquarters reported twice the number of enemies killed. What is not debated is that the imperial city was utterly destroyed, making over 100,000 people homeless and terrorized.

Medals of Honor, Battle of Huế

CWO Frederick Ferguson, U. S. Army

GySgt John L. Canley, USMC

SSgt Clifford Sims, U.S. Army

SSgt Joe Hooper, U.S. Army

Sgt Alfredo Gonzalez, USMC