The Quế Sơn Valley, located in Quảng Nam Province, is bounded by mountain ranges north, south, and west. It extends some 24 miles from east to west from Route 1 to Hiệp Đức. The Ly Ly River and Routes 534 and 535 traverses most of the valley’s length. In 1965/1966, the valley supported a Vietnamese population of around 60,000 farmers and salt miners. Whoever held Quế Sơn Valley owned the keys to the struggle for the I Corps Tactical Zone (I CTZ).

The struggle for the Quế Sơn Valley began in December 1965 (Operation Harvest Moon) and February 1966 (Operation Double Eagle II). Brigadier General William A. Stiles, USMC, reported to the 1st Marine Division in late April to assume the duties of Assistant Division Commander, 1stMarDiv. Shortly after his arrival, the Division Commander directed Stiles to assume command of Task Force X-Ray. His mission was to plan for and direct a reconnaissance-in-force in the region of Đỗ Xá, South Vietnam.[1]

In June, the Commanding General III Marine Amphibious Force and Commanding General 1stMarDiv received intelligence information compiled by the U.S. Military Advisory Command, Vietnam (USMACV) indicating that a suspected enemy base of operations was operating some thirty miles southwest of Chu Lai, near the western border of I CTZ. MACV placed the headquarters of the enemy’s Military Region v in the area of Đỗ Xá. They had been asking for Marine Corps intervention for several months. Army intelligence had wanted Marines to mount an operation throughout the Valley for several months.

After a few unavoidable delays, Stiles and his staff completed their plan of action but almost immediately became aware of the presence of an entire enemy combat division within the Quế Sơn Valley. The 620th NVA Division operated with three full-strength infantry regiments (3rd, 21st, and 1st VC) in the area straddling the Quang Tin/Quang Nam provinces northwest of Chu Lai. Stiles’ reconnaissance operation, designated Operation KANSAS, was placed on hold until the Marines could address a significant enemy presence close to Chu Lai.

But on June 13, 1966, the III MAF Commander directed the 1stMarDiv to commence an extensive reconnaissance campaign between Tam Kỳ and Hiệp Đức. Stiles was ordered to plan for a joint combat operation with the 2nd ARVN Division. The plan called for the aerial insertion of six Marine reconnaissance teams from the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion and an additional 1st Force Reconnaissance Company team into selected landing zones (LZs) to determine the extent of NVA penetrations.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. Sullivan (1920 – 1995), the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion (1stRecon) commander, would exercise control over all reconnaissance missions. On schedule, a thirteen-man team was airlifted to Nui Loc Son, a small mountain in the center of the Quế Sơn Valley (seven miles northeast of Hiệp Đức. Another eighteen-man team landed on the Nui Vu hill mass that dominates the terrain ten miles west of Tam Kỳ.

These initial landings would be followed up the next morning by two teams to the higher ground south of the valley, two teams to the northwest of the valley, and one in the south of Hiệp Đức. The last team would parachute onto Hill 555, east of the Tranh River. These Marines experienced a single injury as one of the team twisted his ankle upon contact with Terra Firma.

As the operation evolved, the 1st Force Recon Company parachutists were the first to be extracted. After landing, these Marines followed procedure by burying their parachutes and then moved away to establish observation posts. At around 1400 hours, the Marines observed an estimated forty enemy soldiers undergoing tactical training. Four hours later, a woodcutter team appeared with a sentry dog. The animal alerted on the buried parachutes, and a short time later, an enemy combat patrol appeared to be searching for the Marines. The Recon Team Leader, 1stLt Jerome T. Paull, requested that his men be extracted. These Marines were airlifted back to Chu Lai.

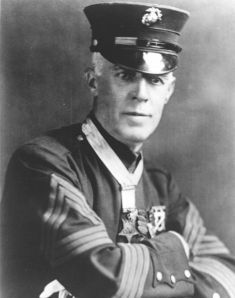

The 18-man team inserted on Nui Vu was led by Staff Sergeant Jimmie E. Howard, USMC. After their insertion on June 13, Howard found the hill an excellent observation platform, and for the next two days, Howard’s team reported extensive enemy activities. This team, supported by an ARVN 105mm Howitzer Battery (located seven miles south of Nui Vu), was able to call in artillery missions on “targets of opportunity.”

Staff Sergeant Howard, a seasoned combat veteran, exercised care to only call artillery missions when an American aircraft spotter or helicopter was in the region, but the enemy was aware of the presence of these Marines and was determined to neutralize the threat.

On the 14th, the NVA began organizing a force to attack the post. On the night of June 15, a U.S. Army Special Forces Team leading a South Vietnamese irregular defense group (popular forces) radioed a warning to General Stiles’ command post (C.P.) — a company-sized unit of between 200 and 250 NVA soldiers closing in on the Marine reconnaissance unit on Hill 448. Word was passed down to the platoon leader, Staff Sergeant Jimmie L. Howard, USMC, through his parent unit, Company C, 1st Recon Battalion, 1st Marine Division.

Later that night, between 2130 and 2330, Lance Corporal Ricardo C. Binns, USMC, detected the sound of troops marshaling for an assault and fired the first shots from his M-14 Rifle. The NVA quickly closed in, surrounding the Marine perimeter. The enemy closed in because they had learned through practical experience that the closer they were to the Marines, the less likely they would become targets of USMC Close Air Support (CAS). Unlike the Air Force, Marine pilots routinely flew CAS missions at tree top level (give or take five inches).

After Corporal Binns opened fire, outpost Marines withdrew from their listening posts to reposition themselves within the rocky knoll. Automatic weapons fire from a DShK machine gun (shown right) and 60mm mortar fire kept the Marines from maneuvering away from their hilltop positions. After their initial fire, the NVA tossed hand grenades into the Marine positions, followed by a short-lived frontal assault. The Marine’s well-aimed rifle fire repelled the enemy’s assault, causing the communists to fall back. After reorganizing, the NVA assaulted the Marines again and again — each time being pushed back by the Marine’s murderous fire.

Near midnight, Staff Sergeant Howard radioed his company commander, Captain Tim Geraghty, to ask for an extraction and close air support. These requests were delayed at the III MAF Direct Air Support Center (DASC).[2] The violence of the enemy attack convinced Howard that his team was being overrun, so he again called for assistance. Colonel Sullivan radioed Howard to reassure him that help was on the way.

At around 0200, a Marine C-47 (DC-3) arrived on station and began dropping flares to light up the area and prepare for the arrival of fixed-wing and rotor gunships. Jet aircraft screamed in and dropped their bombs and napalm within 100 meters of the Marine perimeter. Helicopter gunships from VMO-6 strafed to within twenty meters of the Marine perimeter.

At 0300, enemy ground fire drove off a flight of MAG-36 helicopters that were trying to extract Howard’s Marines. When that attempt failed, Colonel Sullivan informed Howard that he should not expect reinforcements until dawn and urged him to hold on as best he could.

By then, the fight devolved into small, scattered, individual fights between Marine defenders and probing enemies. The NVA, wary of U.S. aircraft, decided against organizing another mass assault but continued to fire at the Marines throughout the night. Enemy snipers had placed themselves close to and above the Marine’s defenses.

Staff Sergeant Howard’s Marines were running out of ammunition; their situation was critical. Howard ordered his men to fire only well-aimed single shots at the enemy. The Marines complied with their team leaders’ instructions but also began throwing rocks at suspected enemy positions, hoping the enemy would think that the Marines were lobbing in grenades. By 0400, every Marine in Howard’s team had been wounded; six Marines lay dead. Staff Sergeant Howard was struck in the back by a ricochet, which temporarily paralyzed his legs. Unable to stand, Howard pulled himself from one fighting hole to the next, encouraging his men and directing their fire.

At dawn on June 16, UH-34s, with Huey gunship cover, successfully landed Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (C/1/5) at the base of Nui Vu. The helicopter piloted by Major William J. Goodsell, the Commanding Officer of VMO-6, was shot down. While Goodsell was successfully evacuated, he later died from his wounds.

Charlie Company encountered enemy resistance as it moved to relieve Howard’s team. When Charlie Company’s lead element reached Howard’s position, he shouted a warning to “get down” because enemy snipers were helping themselves to any Marine that appeared in their rear sight aperture. The company commander, First Lieutenant Marshal “Buck” Darling, later reported that when he arrived at Howard’s position, every Marine still alive had armed themselves with enemy AK-47s taken from dead communists lying within the Marine perimeter.

Everyone associated with the defensive operation assumed that Howard and his men had held off an NVA rifle company. Military intelligence later clarified that Howard’s 18 Marines had held off a battalion of NVA regulars from the 3rd NVA Regiment. The enemy continued to battle the Marines for the hill until around noon and then disengaged. When the enemy pulled out, they left behind 42 dead. Charlie Company lost two KIA and two WIA.

Meanwhile, General Stiles’ completed plan of action involved eight battalions (four Marine and four ARVN) with air and artillery support. The initial assault force included two battalions from the 5th Marines and two Vietnamese Army battalions. Stiles and his Vietnamese counterpart would control the action from Tam Kỳ. Anticipating the need for massive firepower, Stiles prepositioned artillery units from Da Nang and Chu Lai into forward firing positions on Hill 29, west of the railroad line seven miles north of Tam Kỳ.

The 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (3/1) accompanied artillery units from Da Nang and provided security for the artillery positions on Hill 29 and Thang Binh. Artillery support units included HQ Battery 4/11 (command and control), Kilo Battery 4/12 (6 155mm Howitzers at Hill 29), and Provisional Yankee Battery 4/12 (2 155mm Howitzers) at Thang Binh.

On the morning of June 17, the South Vietnamese military high command notified the Marines that the two Vietnamese infantry battalions would not participate in the Marine Corps operation. Accordingly, Lieutenant General Lewis W. Walt (III MAF) delayed Operation Kansas again — and then modified General Stiles’ plan of action.[3] Rather than a multi-battalion heliborne operation in the Quế Sơn Valley, Walt elected to continue the reconnaissance in force. Note: Walt’s decision placed fewer than 1,800 Marines against an entire NVA infantry division.

The Fifth Marines (5thMar) remained at Chu Lai, ready to support the Recon Marines on-call. Stiles continued in command of the operation. He repositioned some of his assets to provide better coverage for the recon teams. On June 18, Kilo 4/11 (4 155mm guns) joined the other artillery units on Hill 29, and an additional provisional battery from the 12th Marines deployed to a new firing position 6,000 meters from Thang Binh. Kilo 4/12 joined the new provisional battery the next day. On June 19, CH-46 aircraft lifted two 105mm howitzers from Chu Lai to the Tien Phuoc Special Forces Camp, some 30 miles distant. Operational control of 3/1 was transferred to the 5th Marines.

With these support units repositioned, Colonel Sullivan shifted his CP to Tien Phuoc. For the next ten days, the reconnaissance battalion (reinforced) continued to conduct extensive patrolling operations throughout the Quế Sơn Valley. Twenty-five recon teams were involved in this operation.

Operation Kansas, which officially began on June 17, ended on June 22nd when General Stiles relocated his command post. Marine infantry participation, with the exception of the relief of Staff Sergeant Howard’s platoon, was confined to a one-company exploitation of a B-52 Arc Light strike on June 21, some 3,500 meters east of Hiệp Đức.[4] Despite Operation Kansas’s official end on June 22, Marines remained in the area for six additional days.

Four of Howard’s Marines were awarded the Navy Cross: Corporal Binns, Hospital Man Second Class Billee Don Holmes, Corporal Jerrald Thompson, and Lance Corporal John Adams. Thompson and Adams, killed in action, were awarded posthumous medals. Silver Star Medals were awarded to the remaining thirteen Marines, four posthumously, along with two Marines from Charlie Company, also posthumously.

Staff Sergeant Howard received a meritorious combat promotion to Gunnery Sergeant and was later awarded the Medal of Honor—our nation’s highest combat award. Howard was eventually promoted to First Sergeant, retired from the Marine Corps in 1977, and became a high school football coach. He passed away in 1993, aged 64.

Notes:

[1] Stiles graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, Class of 1939, and was an officer with extensive combat experience.

[2] The DASC is the principal USMC aviation command and control system and the air control agency responsible for directing air operations directly supporting ground forces. It functions in a decentralized mode of operations but is directly supervised by the Marine Tactical Air Command Center (TACC) or Navy Tactical Air Control Center (NTACC). The parent unit of DASCs is the Marine Air Support Squadron (MASS) of the Marine Air Control Group (MACG).

[3] Lew Walt (1913 – 1989) served in World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam. During his military service, he was awarded two Navy Cross medals, two Navy Distinguished Service medals, the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit (with Combat V), the Bronze Star (with Combat V), and two Purple Heart medals. Following his promotion to four-star general and service as the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, Walt retired in 1971. General Walt passed away on March 26, 1989.

[4] Following the Arc Light strike, Echo Company 2/5 surveyed the strike area and found no evidence of a large body of enemy forces.