Some background …

In 1967, North Vietnamese military officials realized that their war strategy in South Vietnam wasn’t working out quite the way they had hoped. It was time to try something else. The government of North Vietnam wanted a massive offensive, one that would reverse the course of the war. When defense minister and senior army commander General Vo Nguyen Giap[1] voiced opposition to such an offensive, believing that a significant reversal of the war would not be the likely result of such an undertaking, North Vietnamese officials stripped Giap of his position, gave him a pocket watch, and sent him into retirement.

The politburo then appointed General Nguyen Chi Thanh to direct the offensive. At the time, Thanh was commander of all Viet Cong forces in South Vietnam. When General Thanh unexpectedly died, senior politburo members scrambled to reinstate General Giap.

Earlier — in the Spring of 1966 — Giap wondered how far the United States would go in defending the regime of South Vietnam. To answer this question, he executed a series of attacks south of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) with two objectives in mind. First, he wanted to draw US forces away from densely populated urban and lowland areas where the NVA would have an advantage. Second, Giap wished to know if the United States could be provoked into invading North Vietnam.

Both questions seem ludicrous since luring the military out of towns and cities was the last thing he should have wanted, and unless China was willing to rush to the aid of its pro-communist “little brothers,” tempting the US to invade North Vietnam was fool-hardy. In any case, General Giap began a massive buildup of military forces and placed them in the northern regions of South Vietnam. Their route of infiltration into South Vietnam was through Laos. General Giap completed his work at the end of 1967 — with six infantry divisions massed within the Quang Tri Province.

US Army General William C. Westmoreland, commander of the United States Military Assistance Command in Vietnam (COMUSMACV or MACV), led all US and allied forces in Vietnam. Westmoreland responded to Giap’s buildup by increasing US/allied forces in Quang Tri, realizing that if he wanted the enemy to dance, he would have to send his men into the dance hall.

What Westmoreland could not do, however, was invade either North Vietnam or Laos[2]. Realizing this, Giap gained confidence in creating more significant battles inside South Vietnam. But even this wasn’t working out as Giap imagined. Westmoreland was not the same kind of man as French General Henri Navarre, whom Giap had defeated in 1954. For one thing, Westmoreland was far more tenacious, and meeting the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) away from populated areas would allow Westmoreland to make greater use of his air and artillery assets.

In phases, Giap increased North Vietnam’s military footprint in the northern provinces of South Vietnam. One example of this was the NVA’s siege of the Khe Sanh combat base. President Lyndon Johnson was concerned that the NVA was attempting another coup de guerre, such as at Dien Bien Phu, where Navarre was thoroughly defeated. Johnson ordered Khe Sanh held at all costs. With everyone’s eyes now focused on those events, Giap launched a surprise offensive at the beginning of the Tet (Lunar New Year) celebration. He gave his attack order on January 31, 1968. It was a massive assault involving 84,000 NVA and Viet Cong (VC) soldiers executing simultaneous attacks on 36 of 44 provincial capitals, five of the six autonomous cities (including Saigon and Huế), 64 of 242 district capitals, and 50 hamlets.

Giap chose to violate the Tet cease-fire accord because he knew that many South Vietnamese soldiers would be granted leave to celebrate the holiday with their families. It was an intelligent move that gave Giap a series of early successes. VC forces even managed to breach the US Embassy enclosure in Saigon. Within days, however, the offensive faltered as US/ARVN forces turned back the communist onslaught. Heavy fighting continued in Kontum, Can Tho, Ben Tre, and Saigon … but the largest occurred in the City of Huế[3]. The Battle of Huế was the longest and the bloodiest battle of the Tet Offensive.

In 1968, Huế was the third-largest city in South Vietnam; its population was around 140,000, and about a third of those living inside the Citadel, north of the Hương River, which flows through the city.[4] Huế also sat astride Highway One, a major north-south main supply route about 50 miles south of the DMZ. Huế was the former imperial capital of Vietnam. Up to this point, Huế had only occasionally experienced the ravages of war—mortar fire, saboteurs, and acts of terrorism, but a large enemy force had never before appeared at the city’s gates. But, as a practical matter, given the city’s cultural and intellectual importance to the Vietnamese people (and its status as the capital of Thua Thien Province), hostile actions were only a matter of time.

The people who lived in Huế enjoyed a tradition of civic independence dating back several hundred years. The city’s religious monks viewed the war with disdain, but it is also true that few religious leaders felt any attachment to the government in Saigon. They wanted national reconciliation — a coalition where everyone could get along.

Ancient tradition held that Huế had sprung to life as a lotus flower blossoming from a mud puddle. It is a fascinating myth. The city is situated on a bend of the Perfume (Hương) River just five miles southwest of the South China Sea. The river divided Huế into two sections. On the north bank stood the Citadel, a fortress encompassing nearly four square miles (modeled after China’s Forbidden City). The Citadel was shaped like a diamond, its four corners pointing to the cardinal directions of the compass. Stone walls encircled the Imperial City, and just beyond those, a wide moat filled with water. The walls stood 8 meters high and several meters thick.

On the southeastern wall, the Perfume River ran a parallel course, which offered additional protection from that quarter. There were ten gates; four of these (along the southeastern side) were made of carved stone. The remaining walls each had two less elaborate gates. A winding shallow canal ran through the Citadel, from southwest to northeast. Two culverts connected the inner-city canal with those on the outside.

A newer section of the city lay south of the Perfume River. It was the center for residential and business communities, including government offices (and a US Consulate), a university, provincial headquarters, a prison, a hospital, a treasury, and the forward headquarters element of MACV sited within a separate compound. Referred to as “New City,” it was half the size of the old town. It was also called The Triangle because of its irregular shape between the Phu Cam Canal in the south, a stream called Phat Lac on the east, and in the north by the Perfume River. A pair of bridges linked the modern city to the Citadel: the Nguyen Hương Bridge (part of Highway 1) at the eastern corner of the Citadel, and fifteen hundred meters to the southwest was the Bach Ho Railroad Bridge. Another bridge, called the An Cuu Bridge, was a modest arch on Highway 1 that conveyed traffic across the Phu Cam Canal.

Despite Huế’s importance, fewer than a thousand soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were on duty. Security for Huế was assigned to the First Infantry Division (ARVN) under the command of Brigadier General Ngo Quant Truong. The 1st ARVN was headquartered within the fortified Mang Ca compound in the northeast corner of the Citadel.

Over half of Truong’s men were on leave for the holiday when the Giap commenced his offensive at Huế. His subordinate commands’ location was spread along Highway 1 from north Huế to the DMZ. The closest unit of any size to the division CP was the 3rd ARVN Regiment. The regiment’s three battalions were located five miles northwest of Huế. The only combat unit inside the city was a 36-man platoon belonging to an elite unit called the Black Panthers, a field reconnaissance and rapid reaction company. Internal security for Huế was the responsibility of the National Police.[5]

The nearest US combat base was Phu Bai, six miles south on Highway 1. Phu Bai was a major U. S. Marine Corps command post and support facility that included the forward headquarters element of the 1st Marine Division (designated Task Force X-Ray). The Commanding General of Task Force X-Ray[6] was Brigadier General Foster C. LaHue, who also served as the Assistant Division Commander of the 1st Marine Division. Also situated at Phu Bai were the headquarters elements of the 1st Marine Regiment (Stanley S. Hughes, Commanding) and the 5th Marine Regiment (Robert D. Bohn, Commanding). There were also three battalions of Marines: 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (1/1) (Lt. Col. Marcus J. Gravel, Commanding), 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (1/5) (LtCol Robert P. Whalen, Commanding), and 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines (2/5) (LtCol Ernest C. Cheatham, Jr., Commanding).

In addition to the Marines, several US Army commands were present, including two brigades of the 1st Air Cavalry Division (AIR CAV), which included the 7th and 12th Cavalry Regiments (dispersed over a wide area, from Phu Bai in the south to Quang Tri in the north), and the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division at Camp Evans, between Huế and Quang Tri. Operational control of the 1st Brigade was assigned to the 1st Air Cav.

NVA forces included 8,000 well-trained and equipped soldiers. The majority of these were NVA regulars. The NVA was reinforced by six VC main force battalions (between 300 and 600 men each). The field commander of these forces was General Tran Van Quang. The NVA plan called for a division-sized assault on the Imperial City, with other units serving as a blocking force to stop or frustrate the efforts of any allied reinforcing units. True to form, the communists knew all they needed about their civilian and military objectives within the city. VC cadres had also prepared a list of “tyrants” who were to be located and terminated — nearly all of these South Vietnamese civilian and military officials. Added to the lists were US civilians, clergy, educators, and other foreigners. The communists also knew all they needed to know about the weather.

The NVA plan (termed the General Offensive/General Uprising) was designed to incorporate both conventional and guerilla operations intending to destroy any vestige of the South Vietnam government and its Western allies, and if not that, then discredit the enemy and cause a popular uprising among the people. If everything worked according to plan, the Western allies would be forced to withdraw their forces from Vietnam.

A few senior NVA planners thought a popular uprising was highly unlikely; a few more expected that ARVN and US forces would drive the NVA out of the city within a few days —but, of course, such defeatist notions were best left unsaid. Meanwhile, the young, idealistic, gullible soldiers believed the propaganda and went into combat, convinced of a great victory. When these same young men departed their training camps, they had no intention of returning. Many wouldn’t.

The Fight Begins

In January 1968, everyone sensed that something was off-kilter. Tet was approaching. The people were uneasy. The cancellation of the Tet Truce and enemy attacks at Da Nang and elsewhere in southern I Corps dampened the normally festive spirit at Tet.[7] The first indication of trouble came shortly after midnight during the night of January 30-31 — a five-pronged assault on all five provincial capitals in II Corps and the city of Da Nang in I Corps. VC attacks began with mortar and rocket fire, followed by large-scale ground assaults by NVA regulars. However, these were not well-coordinated attacks, and by dawn on January 31, most communists had been driven back from their objectives.

These initial attacks turned out to have been launched prematurely, but while US forces and ARVN units were placed on operational alert, there was no immediate sense of urgency. ARVN commands sent our orders, which canceled all leaves for the Tet holiday, but most of these arrived too late, and besides that, General Truong did not believe the NVA had the intent or capability of attacking Huế City. Allied intelligence kept tabs on two NVA regiments in Thua Thien Province, but there was little evidence of enemy activity in and around Huế City. When Truong positioned his reduced force around the city, he intended to defend the urban areas outside the Citadel.

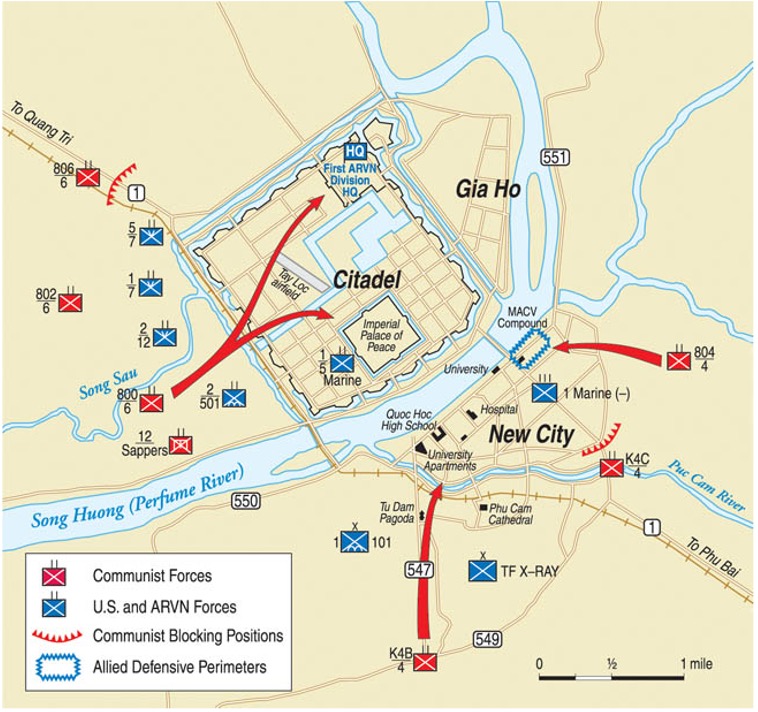

General Truong was not necessarily wrong in his conclusions —he was only misinformed. According to US intelligence, the 6th NVA Regiment (with 804th Battalion) was reported operational 15 miles west of Huế. The 806th Battalion was positioned outside Phong Dien, 22 miles northeast of Huế. The 802nd Battalion was placed 12 miles south of Huế. Analysts also placed the 4th NVA Regiment between Phu Bai and Da Nang. Unknown to anyone, both regiments were en route to Huế. The 6th NVA Regiment’s primary objectives were the Mang Ca headquarters compound, the Tay Loc Airfield, and the Imperial Palace. The 4th NVA Regiment was assigned to attack New City, including the Provincial headquarters, the prison, and the MACV (forward) headquarters compound. NVA planners assigned 200 specific targets between these two regiments, including radio stations, police stations, government officials, recruiting centers, and the Imperial Museum. Viet Cong main force battalions were specifically targeting individuals — those sympathetic to the South Vietnam regime.

On January 30, enemy shock troops and sappers entered the city disguised as simple peasants, their uniforms and weapons concealed in baggage or under their street clothes. VC and NVA regulars mingled with the Tet holiday crowds. Many of these covert agents dressed in ARVN uniforms and then took up pre-designated positions to await the signal to attack. The 6th NVA Regiment was only a few miles from the city’s western edge. About 1900, the Regiment stopped for an evening meal, and regimental officers inspected their troops. The regiment resumed its march one hour later in three columns, each with an objective within the Citadel.

At 2200 hours, Lieutenant Nguyen Van Tan, Commanding Officer of the 1st ARVN Division Reconnaissance Company, was leading a 30-man surveillance mission when a Regional Force Company east of his position reported it was under attack.[8] Remaining concealed, Tan observed two enemy battalions filter past his position toward Huế City. Tan radioed this information back to the 1st ARVN. These were likely the 800th and 802nd Battalions, 6th NVA Regiment. Despite Tan’s report, the communist troops continued toward Huế unmolested.

The NVA country-wide general offensive began at 0300; the only ARVN force inside Huế was the Black Panther Company, responsible for guarding the Tai Loc Airstrip (northwestern corner of the Citadel). By then, large numbers of VC guerillas had already infiltrated the city. In the early morning hours, the enemy took up positions in the town and awaited the arrival of NVA and VC assault troops.

At 0340, the NVA launched a rocket and mortar barrage from the mountains west of the city and followed this up with a three-pronged assault. A small sapper team dressed in ARVN uniforms killed guards and opened the western gate to the Citadel. The lead elements of the assault thus penetrated the city; the 6th NVA Regiment led the attack. As communist fighters poured into Huế, the 800th and 802nd Battalions rapidly overran most of the Citadel. General Truong and his staff held off the attackers at the ARVN compound, and the Black Panther Company held its ground at the eastern end of the airfield. Truong later withdrew the Black Panther company from the airfield to reinforce the ARVN compound. Except for this area, the NVA held the entire citadel, including the Imperial Palace.

The situation was similar across the Perfume River in southern Huế. The sound of explosions awakened allied advisors in the MACV compound. Grabbing any weapon they could get their hands on, advisors were able to repulse the ground assault, which lacked a coordinated effort. When the initial assault faltered, the 804th Battalion, 4th NVA Regiment, encircled the compound and began their siege. Two VC main force battalions seized the Thua Thien Provincial headquarters, the police station, and several other government buildings south of the river. The NVA 810th Battalion took up blocking positions on the city’s southern edge. By dawn on January 31, the North Vietnamese flag was flying over the Citadel, communist troops patrolled the streets, and political officers had begun their purge of South Vietnamese officials and American civilians.

The U. S. Marines

While the NVA were launching their attacks at Huế, the Marine Base at Phu Bai began receiving enemy rockets and mortars targeting the airstrip and Marine and ARVN infantry units. General LaHue started receiving reports of enemy strikes along Highway 1 between the Hai Van Pass and the City of Huế. Altogether, the NVA launched assaults against 18 targets. Intelligence was jumbled; no one was sure what was happening or where. LaHue knew that the 1st ARVN and MACV compounds had been hit, and because of the attack against the Navy’s LCU facility, all river traffic had ceased.

Meanwhile, General Truong realized that, at best, he had a tenuous hold on his headquarters. He ordered the 3rd Regiment (reinforced by two ARVN airborne battalions and a troop of armored cavalry) to fight into the Citadel from the northeast. The regiment finally arrived in the late afternoon, but only after intense fighting and a costly fight in terms of soldiers killed and wounded. Pleas for reinforcements at the MACV compound went unanswered because none of the senior commanders knew the extent of the enemy’s strength or their success in entering Huế.

Lieutenant General Hoang Xuan Lam (Commander, ARVN Forces I CTZ) and Lieutenant General Robert Cushman (CG III Marine Amphibious Force (MAF)) began ordering subordinate commands to prevent enemy reinforcements from reaching the city. The NVA had the same idea—to prevent Western allies from entering the city. The NVA 806th and 810th blocked positions in southern Huế and along Highway 1.

Having received no reliable intelligence, General LaHue surmised that the attacks might have been a diversionary strike. General LaHue, who was only newly assigned to the Phu Bai area, was still unfamiliar with this tactical region (also, TAOR), let alone the fast-developing situation in Huế City.[9] This wasn’t the only problem for the Marines. Task Force X-Ray was created to help manage a major shift in the locations of the various combat elements of the First Marine Division and Third Marine Division, necessitated by MACV’s realignment of forces in I Corps.[10]

Colonel Bohn arrived at Phu Bai with General LaHue on 13th January. 1/1 under Colonel Gravel began making its move from Quang Tri at about the same time. His subordinate units, Charlie Company and Delta Company, reached Phu Bai on January 26, while Bravo Company and Headquarters Company arrived three days later. Alpha Company, Captain Gordon D. Batcheller, Commanding, arrived piecemeal. Two of his platoon commanders failed to arrive with their platoons, and a third platoon commander was attending leadership school in Da Nang.[11]

On January 30th, the First Marine Regiment (1st Marines) replaced the 5th Marines in operational responsibility for the Phu Bai TAOR. Colonel Hughes formally took operational control of the 1st Battalion (consisting of Company B, C, and D). In effect, Hughes commanded a paper regiment with barely a single battalion of Marines.

1/1 had already relieved 2/5, providing security on various bridges along Highway 1 and other key positions. When Company A finally arrived at Phu Bai on January 30, it was designated battalion reserve (also Bald Eagle Reaction Force). 2/5 moved into the Phu Loc sector and assumed responsibility for the area south of the Truoi River and east of the Cao Dai Peninsula. 1/5 retained responsibility for the balance of the Phu Loc region, extending to the Hai Van Pass.

At around 1730 hours on January 30, a Marine Recon unit (code name Pearl Chest) made lethal contact with what was believed to be an NVA company moving north toward Huế, resulting in around 15 enemy killed in action (KIA). After the unit fell back, it regrouped and encircled the Marines. Poor weather prevented Allied air support; the Recon Marines called for relief. LtCol Robert P. Whalen, commanding 1/5, sent his Bravo Company to relieve the Recon team. The NVA attacked Bravo Company as it approached the location of the embattled Recon Marines. Company B proceeded slowly with known enemies in the area and no understanding of how many. Whalen requested Bohn to send additional reinforcements from 2/5 so as not to diminish his battalion’s ability to defend the town of Phu Loc.

Colonel Bohn tasked Cheatham to send in a reinforcing company. Cheatham assigned this mission to Fox Company 2/5 (Captain Michael P. Downs, Commanding). NVA units ambushed Fox Company as it moved into 1/5’s sector. This action occurred at around 2300 hours, with Marines suffering one KIA and three wounded in action (WIA). After this contact, the NVA faded into the night. Fox Company secured an LZ to evacuate the injured and then returned to the 2/5 perimeter.

Realizing that his force was thin — and that his meager force could not sustain a significant engagement, Colonel Hughes ordered the Recon team to break out and return to Phu Bai. Whalen also directed Bravo Company to return to base. Colonel Bohn was puzzled about the purpose of these engagements.

As NVA units assaulted Huế City, they also attacked the Marines at Phu Bai with rockets and mortars, targeting the airstrip, known Marine positions around the airfield, and nearby Combined Action Platoons (CAPs) and local Popular Forces/Regional Forces (PF/RF) units.[12] An NVA company-sized unit attacked the South Vietnamese bridge security detachment along with CAP Hotel-Eight. LtCol Cheatham ordered Hotel Company 2/5 (Captain G. Ronald Christmas, Commanding) to relieve the embattled CAP unit. Marines from Hotel Company caught the NVA in the act of withdrawing from the CAP enclave and took it under fire. Seeing an opportunity to trap the NVA unit, Cheatham reinforced Hotel Company with his command group and Fox Company, which had just returned from its Phu Loc operation.

With his other companies in a blocking position, Cheatham hoped to catch the enemy against the Truoi River. However, after initiating the engagement with the NVA unit, events inside Huế City interrupted his plans. At around 1030 on January 31, Golf Company 2/5 was ordered to assume Task Force X-Ray reserve. The company detached from 2/5 and headed back to Phu Bai. Later that day, 2/5 also lost operational control of Fox Company, which allowed the NVA units to complete their withdrawal. Hotel and Echo Companies established night defensive positions.

While 2/5 engaged NVA along the Truoi River and Phu Loc, 1/1 began to move into Huế City. Task Force X-Ray had received reports of enemy strikes all along Highway 1 between Hai Van Pass and Huế. Eighteen separate attacks had occurred against everything from bridges to CAP units. With Alpha Company 1/1/ as Phu Bai reserve, Colonel Hughes directed Gravel to stage Alpha Company for any contingency. At 0630 on January 31, Hughes ordered Alpha Company to reinforce the Truoi River Bridge. All that the company commander knew was that he was to strengthen ARVN forces south of Phu Bai.

What occurred over the next several hours is best described as a “cluster fuck.” Alpha Company was convoyed to liaison with ARVN units. There were no ARVN units. The company commander encountered a few Marines from a nearby CAP unit and was told that Beau coupé VC were moving toward Huế. Gravel then ordered Batcheller to reverse course and reinforce an Army unit north of Huế. General LaHue rescinded that order, and Alpha Company was then ordered to assist a CAP unit south of Phu Bai. Thirty minutes later, Task Force X-Ray directed Alpha Company to proceed to the Navy LCU ramp to investigate reports of an enemy assault. In effect, the Marines of Alpha Company were being ground down by false starts.

Up to this point, the battle of Huế had been a South Vietnamese problem. General LaHue had little worthwhile information, and Alpha Company continued north toward Huế. The convoy met up with four tanks from the 3rd Tank Battalion. Batcheller invited the tanks to join him, and they accepted. Alpha Company, now reinforced with M-48 tanks, moved toward the MACV compound.

As Alpha Company approached the southern suburbs, the Marines came under increased sniper fire. At one village, the Marines were forced to dismount their vehicles and conduct clearing operations before proceeding further. The convoy no sooner crossed the An Cuu Bridge, which spanned the Phu Cam Canal into the city, when they were caught in a murderous crossfire from enemy automatic weapons and rockets. NVA were on both sides of the road. The lead tank commander was killed. Alpha Company pushed forward —albeit cautiously. Batcheller maintained “sporadic” communications with Gravel at Phu Bai. For the most part, the only thing Batcheller heard on the artillery and air nets were the voices of frantic Vietnamese. When Alpha Company reached the causeway, they once more came under sniper fire. Batcheller was seriously wounded. Gunnery Sergeant J. L. Canley assumed command of the company.[13]

Colonel Hughes requested permission from LaHue to reinforce Alpha Company. The only available reinforcing units were Headquarters & Service Company (H&SCo), 1/1, and Golf Company, 2/5. Colonel Gravel’s battalion was strung out from Phu Bai to Quang Tri (a distance of 46 miles). For whatever reason, Gravel had never met his Golf Company Commander, Captain Charles L. Meadows. Worse, Captain Meadows had no idea what was happening or what his upcoming mission would entail. All Meadows understood was that Golf Company would help escort the Commanding General to the 1st ARVN Division and back to Phu Bai.

Gravel’s hodge-podge column reached Alpha Company in the early afternoon. Gravel assumed control of the tanks but sent the trucks loaded with WIAs back to Phu Bai (including Captain Batcheller). With tanks taking point, Alpha Company, H&S Company, and Golf Company —in that order— raced toward the MACV compound. They arrived at about 1500 hours. By this time, the enemy had pulled back. Gravel met with the US Army senior advisor at the MACV compound, Colonel George O. Adkisson. Gravel was trying to understand the enemy situation, but this conversation may have ended with Gravel having even less understanding than when the discussion had begun.

Gravel ordered Alpha Company to establish a defensive perimeter at the MACV compound. With armor reinforcements from the Marines and 7th ARVN, Gavel took Golf Company in tow and attempted to cross the main bridge over the Perfume River. Marine armor was too heavy for the bridge, so Gravel left them on the south bank of the river. Available Vietnamese M-24 tank crews refused to go across the bridge.[14] Gravel directed two platoons to cross the bridge, but they were saturated with enemy fire when they reached the other side. Realizing he was outgunned, Gravel withdrew his Golf Company and returned to the MACV compound. One-third of Company G’s Marines were killed or wounded in this engagement.

The Americans still had scant information about the situation in Huế at 2000 hours. If General LaHue was confused, he knew far more about the situation than did Westmoreland. According to Westmoreland’s message to the JCS Chairman, three NVA companies were inside the Citadel, and a battalion of Marines had been sent in to clear them out.

The Struggle —

On February 1, senior allied commanders agreed that the 1st ARVN Division would assume responsibility for the Citadel while Task Force X-Ray would clear the New City. General LaHue ordered Gravel to advance from the MACV compound to the Thua Thien provincial headquarters and the prison — a distance of about six city blocks. General LaHue briefed reporters, saying, “… very definitely, we control the city’s southside.”

In reality, the Marine footprint was too small to control anything. CG III MAF secured Westmoreland’s permission to send in the Cavalry. Major General John J. Tolson, commanding the First Cavalry Division (Airmobile), intended to insert his Third Brigade from Camp Evans into the sector west of Huế City. Two battalions would be airlifted into the northwest sector: 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, and 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry (and Brigade CP). Their mission was to close off the enemy’s supply line into Huế. Additionally, the 2nd Battalion, 101st Airborne, would cover security for Camp Evans, and the division’s First Brigade would continue operations in Quang Tri Province. At mid-afternoon on February 2, CAV 2/12 landed 10 miles northwest of Huế and began pushing toward the city.

But on February 2, the Marines were still struggling. There was some minor progress, but only after a 3-hour firefight. 1/1 finally reached the university, and the Army radio center was relieved. During the night, NVA managed to destroy the railroad bridge across the Perfume River. Commanding Hotel Company 2/5, Captain Ron Christmas crossed the An Cuu Bridge at around 1100. Hotel Company was reinforced with Army trucks equipped with Quad-50 machine guns and two ONTOS, each armed with six 106mm recoilless rifles, which devastated enemy positions wherever they were found.

Gravel launched a two-company assault toward his two objectives. The enemy stopped the attack as effectively as a brick wall, and the Marines withdrew to the MACV compound. It was then that General LaHue realized that he had underestimated the enemy’s strength. Shortly after noon, LaHue gave Colonel Hughes tactical control of Marine forces in the southern city. Hughes promised Gravel reinforcements and directed that he commence “sweep and clear operations: destroy the enemy, protect US nationals, and restore that portion of the city to US Control.”

On the afternoon of February 2, Hughes decided to move his command group from Phu Bai into Huế, where he could more directly control the battle. Accompanying Hughes in the convoy was Lt. Col. Ernest Cheatham, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, who, up until then, had been sitting frustrated in Phu Bai while three of his companies (F, G, and H) fought in Huế under Gravel’s command.[15]

Hughes quickly established his command post in the MACV compound. The forces at his disposal included Cheatham’s three companies from 2/5 and Gravel’s depleted battalion consisting of A Company, 1/1; a provisional company made up of one platoon of B Company, 1/1; and several dozen cooks and clerks who had been sent to the front to fight alongside the infantry.

Endnotes:

[1] General Giap defeated the Imperial French after eight years of brutal warfare following the end of World War II.

[2] The United States did deploy covert and special forces into Laos at a later time.

[3] Pronounced as “Way.”

[4] The Hương River (also Hương Giang) crosses the city of Huế in the central province of Thừa Thiên-Huế. The translation for Hương is Perfume. It is called the Perfume River because, in autumn, flowers from upriver orchards fall into the river, giving it a perfume-like aroma. Of course, this phenomenon likely happened a thousand years ago because, in 1968, the river smelled more like an open sewer.

[5] The National Police were sometimes (derisively) referred to as white mice. They were un-professional, non-lethal, timid, and about a third of them were giving information to the enemy on a regular basis.

[6] Task Force X-Ray went operational on 13 January 1968.

[7] In 1962, South Vietnam was divided into four tactical zones: CTZs or numbered Corps. These included I CTZ (Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin); II CTZ (Quang Ngai, Kontum, Pleiku, Binh Dinh, Phu Yen, and Phu Bon); III CTZ (16 provinces); IV CTZ (13 provinces), and the Capital Zone (Saigon and Gia Dinh provinces).

[8] South Vietnamese militia.

[9] Equally valid for most subordinate commanders and units at Phu Bai.

[10] Operation Checkers was a shift in responsibility for guarding the western approaches to Huế City. To that end, the 1st and 5th Marine Regiments moved into Thua Thien Province from Da Nang. It was a massive shift of American military units, which also involved US Army units operating in I Corps. This shifting of major subordinate commands played right into General Giap’s hands.

[11] I will probably never understand why sending a recently commissioned officer to a leadership school in Vietnam was necessary.

[12] Thirteen-man rifle squads with medical support and reinforced by Vietnamese militia platoons assigned to provide area security within rural hamlets. See Also: Fix Bayonets on 02/05/2016 (series)

[13] Initially awarded the Navy Cross medal, the award was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2017.

[14] The M-24 Chafee light tank weighed 18 tons; the M-48 Patton tank weighed 40 tons. The Vietnamese tank crews were likely ordered not to attempt to cross the bridge.

[15] At this time, Ernie Cheatham was a 38-year-old veteran of two wars and 14 years removed from a professional football career. The Pittsburgh Steelers picked him in the 1951 draft. He put his NFL career on hold to fight in the Korean War, afterward suiting up as a defensive tackle with the Steelers for the 1954 season. But after being traded to the Baltimore Colts, Cheatham left professional football and rejoined the Marine Corps. Lieutenant General Ernest C. Cheatham retired from active service in 1988; he passed away on 14 June 2014.