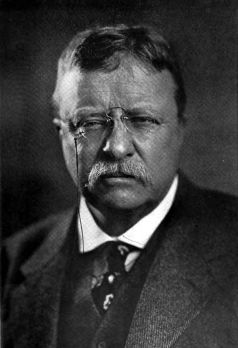

Arguably, the most important action President Theodore Roosevelt ever took in foreign affairs related to the construction of the Panama Canal. It was controversial abroad —it was controversial at home. Those who opposed the canal claimed that Roosevelt’s actions were unconstitutional. If true, then so too were Thomas Jefferson’s actions when he acquired the Louisiana Territory. At different times, the congressional do-nothings accused Roosevelt of usurping their authority. They must not have known Roosevelt very well; he was a man of action.

Some background…

A canal across the isthmus of Panama was first discussed in 1534, when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain ordered a survey for a route through the Americas that would shorten the voyage for ships traveling between Spain and Peru. In 1668, the British physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne speculated that such an undertaking would be a good idea; after all, it only involved “but a few miles” across the isthmus. A little more than 100-years later, Thomas Jefferson (then US minister to France), suggested to the Spanish that they proceed with their project; after all, it would be far less treacherous than sailing ships around the tip of South America. Besides, he added, the tropical ocean currents would naturally widen the canal thereafter and it would be easy to maintain it.

By the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, numerous canals were constructed in other countries. Engineers were learning how to do this. The success of the Erie Canal in the 1820s was inspiring, and the collapse of the Spanish Empire in the New World led to a surge of American interests in building an inner-oceanic canal.

Of course, in the first eighty-years following independence from Spain, Panama was a department (province) of Colombia. Panama voluntarily joined Colombia in 1821. It was not a happy marriage, however, and the Panamanians made several attempts to secede, notably in 1831 and again during the Thousand Days War of 1899-1902. Among the indigenous people, the struggle was one for land rights [1] under the leadership of Victoriano Lorenzo [2].

Earlier, in 1826, American officials attempted to open negotiations with Gran Colombia (present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama) to gain a concession for the construction of a canal. Fearing domination by an American presence, Gran Colombian president Simón Bolívar and officials of New Granada politely declined American offers.

Earlier, in 1826, American officials attempted to open negotiations with Gran Colombia (present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama) to gain a concession for the construction of a canal. Fearing domination by an American presence, Gran Colombian president Simón Bolívar and officials of New Granada politely declined American offers.

The British also opened discussions about constructing an Atlantic-Pacific canal in 1843 but in the absence of any Colombian interest, no plan was ever formulated. Moreover, negotiations to construct a isthmus-wide railroad were similarly ignored. However, in 1846, New Granada officials and the United States negotiated the so-called Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty. The treaty granted the United States transit rights through Panama, and, while acknowledging the right of the United States to protect these transit rights, also pledged America’s neutrality in matters pertaining to the internal affairs of New Granada.

With the discovery of gold in California in 1848, renewed interest in a sea-to-sea canal was undertaken by William H. Aspinwall, an American shipping magnate. His efforts resulted in a steamship route from New York City to Panama, and from Panama to San Francisco, with an overland portage through Panama. It was one of the fastest routes between San Francisco and the East Coast of the US —about 40 or so days in total. Nearly all of the gold taken from California was shipped through this routing. The ever-competitive Cornelius Vanderbilt similarly established steamship routes to Nicaragua [3] and an overland route to the Pacific.

Between 1850-55, the United States constructed a railroad in Panama; it became a vital link in trade (and later, the route for the Panama Canal). Late in 1855, the engineer William Kennish published a report entitled The Practicality and Importance of a Ship Canal to Connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Twenty-two years later, two French engineers surveyed the route and submitted a French proposal for a canal through Panama.

In March 1885, Colombia reduced its military presence in Panama in order to address rebellions in other areas. With a reduced military footprint, Panamanian rebels began an insurgency. The US Navy was dispatched to protect US personnel and property. Establishing a base of operations at the city of Colón, the American Navy was soon challenged by the Chilean Navy, who at the time had the strongest naval force in the Americas. The Chilean cruiser Esmeralda was dispatched to seize and control Panama City. Esmeralda was instructed to “stop by any means possible the eventual annexation of Panama by the United States.” Note: I’m not quite sure how Chile intended to accomplish this with their ships on the Pacific Coast, and most of the US Navy on the Caribbean side of Panama.

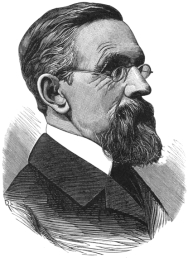

Meanwhile, undaunted, the French proceeded with their Panama Canal operations between 1881-94. Ferdinand de Lesseps [4] was able to raise considerable funds for this undertaking, mostly from revenues generated by the Suez Canal, but in practical terms, the undertaking in Panama was far more complex than the Suez project due to the terrain and tropical climate. As time progressed, the French discovered that they were completely unprepared for such an undertaking in Panama. There were no similarities between the Suez Canal and one like it in Panama. Tropical Panama was a nest of poisonous snakes, spiders, and insects. The rainy season transformed the Chagres River into a raging torrent exceeding ten feet above normal in depth. Moreover, Panama was a land of malaria and other diseases. By 1884, the death rate among French workers averaged 200-men per month. Labor recruiters in France downplayed these conditions by not mentioning them.

Eventually, French money ran out. By 1889, the French had expended $287-million; twenty-two thousand men died from diseases and accidents, and more than 800,000 investors lost their money, which must have been devastating. Work was suspended on 15 May 1889; the scandal became known as the Panama Affair, and those deemed responsible were hauled into French courts —including Gustave Eiffel [5]. Despite this setback, another company was formed in 1894, but its efforts were mostly confined to managing the Panama Railroad, maintaining costly French equipment, and the sale of idle assets. By then, the French were hoping to recoup $109-million. Eventually, its manager, Phillipe Bunau-Varilla [6] became convinced that canal efforts should pursue a lock-and-lake project rather than a sea-level canal modeled after the Suez project.

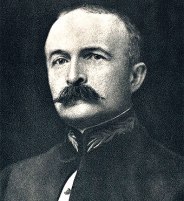

In 1898 Manuel Antonio Sanclemente was elected President of Colombia; José Manuel Marroquin-Ricaurte became his Vice President. On 31 July 1900, Marroquin executed a coup d’état by imprisoning Sanclemente at a location a few miles outside of Bogota. Due to the mysterious disappearance of the President, Marroquin declared himself the sole power in Colombia. In plain language, he became a dictator. The absence of Sanclamente from the capital became permanent upon his death in prison in the year 1902.

The (centralist) Colombian constitution of 1886 denied to Panama the right of self-government; all power was vested within the Colombian regime. When Panamanians declared their independence on 3 November 1903, there was no Colombian Congress. As we will see, Marroquin’s coup d’état did not work out to the overall best interests of the Colombian people.

From the American perspective in 1900, if there was any lessons to be learned from the Spanish-American War, it was that the United States needed a canal somewhere in the Western Hemisphere. The question to be answered was “where.” There were two possibilities: a canal across the isthmus of Panama, or a canal across Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, in order to liquidate French interests in Panama, project manager Phillipe Bunau-Varilla wanted $100-million; eventually, he would end up settling for $40-million.

In 1902, the United States Senate voted in favor of the Spooner Act, a commitment to pursue the Panamanian option —provided that the US could obtain the necessary rights from Colombia. President Marroquin authorized his Ambassador to negotiate a treaty with the United States. Thus, on 22 January 1903, US Secretary of State John Hay and Colombian Charge-de-affairs Dr. Tomás Herrán signed a treaty for the construction of a canal in Panama. Colombia would gain $10-million and an annual payment, and the United States would achieve a renewable lease in perpetuity for the land proposed for the canal. The US Senate ratified the treaty in March.

President Marroquin wielded absolute power in Colombia. It was entirely up to him whether to accept the Hay-Herrán accord or reject it. He decided to reject it —and in order to provide an excuse for doing so, he devised the plan of summoning a special session of Congress —a puppet congress that would do as they were told.

By July 1903, when the course of internal Colombian opposition to the Hay-Herrán Treaty became obvious, a revolutionary junta emerged in Panama. The junta was led by José Augustin Arango, an attorney for the Panama Railroad Company. He was aided by Manuel Amador Guerrero and Carlos C. Arosemena, all of whom represented prominent Panamanian families. Arango was the brain of the revolution; Amador was the junta’s visibly active leader.

With financial assistance arranged by Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French national representing the interests of de Lesseps’s company, native Panamanian leaders conspired to take advantage of the United States’ interest in a new regime on the isthmus.

In August 1903, Theodore Roosevelt became convinced that Colombia was likely to repudiate the agreed-to treaty. At the President’s direction, Secretary Hay, personally and through his Minister [7] at Bogota, repeatedly warned Colombia that grave consequences might follow a rejection of the treaty. There were two possibilities: one was that Panama would remain loyal to Colombia. In this case, Roosevelt was prepared to occupy the isthmus of Panama and dig his canal anyway. Subsequently, Roosevelt and Hay met with Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, who informed the president of the likelihood of a revolt by Panamanian rebels, whose desire it was to sever their ties to Colombia. Bunau-Varilla expressed his hope that should such a thing occur, that the United States would support Panama.

This information was confirmed on 16 October by two US Army officers (Captain Humphrey and Lieutenant Murphy), who had recently returned to Washington from Panama. They informed President Roosevelt that, in their opinion, Panama would most-assuredly revolt against the Colombian government. The Panamanian people were united in their criticism of the government in Bogota; the people were disgusted by Marroquin’s silence on the pending treaty —but that Panamanians would likely await the results of Colombia’s puppet congress before making their move —sometime around the end of the month. President Roosevelt then directed the Navy to station warships at several locations in Panama and be ready to respond to any crisis that may arise.

The possibility of ratification did not wholly pass away until the close of the session of the Colombian Congress on the last day of October. To no one’s surprise, Colombia’s legislature unanimously voted to reject the treaty. Having thus voted, the Congress was immediately dismissed.

Panama declared its independence on 3 November 1903. President Roosevelt enthusiastically recognized the new government on 4 November. US warships blocked sea lanes against any possible Colombian troop movements on 5 November. Meanwhile, in Panama, practically everyone on the isthmus, including Colombian troops stationed there, joined the revolution. Initially, there was no bloodshed. But on 6th November four hundred new Colombian troops were landed at Colón. USS Nashville arrived at Colón at about the same time. When the Colombian commander foolishly threatened the lives of Americans in Colón, Nashville’s commanding officer landed his Marines and sailors to protect them. Through a mixture of firmness and tact, Commander Hubbard not only prevented any assault on American citizens, but he also persuaded the Colombian military commander to reembark his troops for Cartagena. On the Pacific coast, a Colombian ship shelled Panama City; one man was killed —the only life lost in the entire revolution.

On 16 December, the Marines from Nashville were relieved by a 400-man Marine Battalion from USS Dixie under the command of Major John A. Lejeune [8], USMC.

“No one connected with the American Government had any part in preparing, inciting, or encouraging the revolution, and except for the reports of our military and naval officers, which I forwarded to Congress, no one connected with the Government had any previous knowledge concerning the proposed revolution, except such as was accessible to any person who read the newspapers and kept abreast of current questions and current affairs. By the unanimous action of its people, and without the firing of a shot, the state of Panama declared themselves an independent republic. The time for hesitation on our part had passed.“

—President Theodore Roosevelt

The rights granted to the United States in the so-called Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty were extensive. They included a grant “in perpetuity of the use, occupation, and control” of a sixteen-kilometer-wide strip of territory and extensions of three nautical miles into the sea from each terminal “for the construction, maintenance, operation, sanitation, and protection” of an isthmian canal.

The United States was also entitled to acquire additional areas of land or water necessary for canal operations and held the option of exercising eminent domain in Panama City. Within this territory, Washington gained “all the rights, power, and authority . . . which the United States would possess and exercise if it were the sovereign . . . to the entire exclusion” of Panama.

The Republic of Panama became a de facto protectorate of the United States through two provisions: the United States guaranteed the independence of Panama and received in return the right to intervene in Panama’s domestic affairs. In exchange for these “rights,” the United States was to pay the sum of $10 million and an annual payment (beginning 9 years after ratification), of $250,000 in gold coin. The United States also purchased the rights and properties of the French canal company for $40 million. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter agreed to relinquish US control of the Panama Canal Zone effective at midnight on 31 December 1999. Carter’s action was the end of a process that began at the direction of President Lyndon Johnson in 1967.

Unsurprisingly, Colombia was the harshest critic of United States foreign policy at the time —but President Roosevelt wasn’t quite finished with Colombia just yet …

Continued next week …

Sources:

- Wicks, D. H. “Dress Rehearsal: United States Intervention on the Isthmus of Panama, 1886. Pacific Historical Review, 1990

- Collin, R. H. Theodore Roosevelt’s Caribbean: The Panama Canal, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Latin American Context (1990)

- Graham, T. The Interests of Civilization: Reaction in the United States Against the Seizure of the Panama Canal Zone, 1903-1904. Lund Studies in International Relations, 1985.

- Nikol, J. and Francis X. Holbrook, “Naval Operations in the Panama Revolution, 1903.” American Neptune, 1977.

- Turk, R. “The United States Navy and the Taking of Panama, 1901-1903.” Military Affairs, 1974.

- Hendrix, H. J. Commander, USN.“TR’s Plan to Invade Colombia.” S. Naval Institute, Proceedings Magazine.

Endnotes:

[1] Hispanic society was nothing if not harsh. If you weren’t born into wealth (which is to say, entitled to land), then you would never achieve a higher station in life. It remains that way to this very day.

[2] The political struggle in Panama was one between federalists and centralists following independence from Spain. Under the centralist regime, Panama was established as the Department of the Isthmus; during federalist regimes, it was the Sovereign State of Panama.

[3] The genesis, perhaps, of America’s problem with Nicaragua. At this time, the Nicaraguans (wisely) did not trust the motives of the American government.

[4] Vicomte de Lesseps (1805-1894) was a French diplomat, entrepreneur, developer of the Suez Canal, and the Chief Operating Officer for the Panama Canal project.

[5] Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923) was a French civil engineer and a graduate École Centrale Paris. He made his name building various bridges for the French railway network, most famously the Garabit viaduct. He is best known for the world-famous Eiffel Tower, built for the Universal Exposition in 1889 in Paris and his contribution to the construction of the Statue of Liberty in New York.

[6] Bunau-Varilla (1859-1940) was a French engineer, soldier, diplomat, and entrepreneur. Through American lawyer William Nelson Cromwell, he became quite influential with Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State, John Hay.

[7] American diplomats accredited to foreign governments from the time of Benjamin Franklin through the late-nineteenth century held the rank of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, or in abbreviated terms, “Minister.” Within the diplomatic corps, the term Ambassador (short for Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary) is a diplomatic agent of the first class. The term Ambassador has become the generic title for the chief of a diplomatic mission. Before the twentieth century, only major powers sent and received ambassadors. The term “extraordinary” was originally applied to an envoy sent on a special mission, as opposed to “ordinary,” which meant an envoy in residence. Today the term Extraordinary is widely used in diplomatic circles. The term “plenipotentiary” originally meant having the authority to conduct normal diplomatic business, as opposed to the function of negotiating treaties, which required special authority.

[8] John A. Lejeune later served as Commanding General, US 2nd Army Division in World War I and the Thirteenth Commandant of the U. S. Marine Corps.