Background

The Mahabharata is an ancient epic poem that offers philosophical discourses interwoven in the stories of two families during a time of great stress on the Indian subcontinent. It may date 5,000 years ago, but there is considerable debate about its exact dating. Within the Mahabharata is a discussion between ruling brothers concerning what constitutes acceptable behavior on a battlefield. The debate involves the concept of proportionality:

“One should not attack chariots with cavalry; chariot warriors should attack chariots. One should not assail someone in distress, neither to scare him nor to defeat him. War should be waged for the sake of conquest; one should not be enraged toward an enemy who is not trying to kill him.”

The Old Testament book of Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the ancient Torah, also called the words of Moses, is believed to be around 3,300 years old. Verse 19 tells us:

“When you besiege a city for a long time, making war against it in order to take it, you shall not destroy its trees by wielding an axe against them. You may eat from them, but you shall not cut them down. Are the trees in the field human that they should be besieged by you? Only trees that you know are not trees for food you may destroy and cut down, that you may build siege works against the city that makes war with you, until it falls.”

The preceding are examples of ancient “laws of warfare.” In modern times, such laws are a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war and the conduct of warring parties. The laws define sovereignty, nationhood, states, territories, occupation, and other “critical” aspects of international law, such as declarations of war, acceptance of surrender, treatment of prisoners, military necessity, and distinction and proportionality. There are also prohibitions on certain weapons that may cause unnecessary human suffering.

War crimes are violations of the laws of war that give rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants, such as the intentional killing of civilians, prisoners of war, torture, taking hostages, unnecessarily destroying civilian property, perfidy, rape, pillaging, conscription of children, and refusing to accept surrender. In the modern sense, laws of war have existed since 1863, codified during the American Civil War.

During Japan’s imperialist expansion, militarism had a significant bearing on the conduct of the Japanese Armed Forces before and during the Second World War. At that time, following the collapse of the shogunate, Japanese Emperors became the focus of national and military loyalty. Japan, and other world powers, did not ratify the Geneva Convention of 1929, which sought to regulate the treatment of prisoners of war. Japan did ratify earlier conventions, however, in 1899 and 1907. An Imperial proclamation in 1894 instructed Japanese soldiers to make every effort to win a war without violating international laws. History reflects that the Japanese observed these rules after 1894 and during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

According to apologists, pre-World War II Japanese servicemen were trained to observe the Code of Bushido, which extols to every serviceman that there is no greater honor than to give up their lives for their Emperor, and nothing is more cowardly than to surrender to one’s enemy. This argument seeks to explain why Japanese servicemen in World War II mistreated POWs. The POWs were contemptible to the Japanese because they were “without honor.” When the Japanese murdered POWs, beheaded them, and drowned them, it was acceptable because by surrendering, the POWs had forfeited their right to dignity or respect. However, the apologists do not seem able to explain using POWs for medical experiments or as guinea pigs for chemical and biological weapons.[1]

The Japanese military between 1930-1945 is often compared to the German army of about the same period because of the sheer scale of destruction and suffering both armies caused. According to Sterling Seagrave, a noted historian, Japan’s criminal conduct began in 1895 when the Japanese assassinated Korean Queen Min. He tells us that estimates of between 6-10 million murdered people, a direct result of Japanese war crimes, is exceedingly lower than the actual number of people the Japanese killed. He estimates between 10-14 million would be closer to the truth.

According to the Tokyo Tribunal, Japan’s death rate of Chinese held as POWs was considerably higher than the average (as a percent) because Emperor Hirohito removed the protections accorded them under international law in 1937. After 1943, a similar order was issued to the Imperial Japanese Navy to execute all prisoners taken at sea.

In addition to charges (and convictions) for the torture of POWs, the Tokyo Tribunal also charged Japanese war veterans with executing captured airmen, cannibalism, starvation, forced labor, rape, looting, and perfidy.[2] Japanese Kamikaze pilots routinely attacked hospital ships marked with large red crosses, a tell-tale sign that they were noncombatant ships. Some have suggested that Kamikaze pilots did this to escape being shot down before they could damage an enemy vessel.

Trial and punishment

After Japan’s surrender, on 29 April 1946, the International Military Tribunal (Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal) began proceedings to try certain Japanese personnel for war crimes. The Tribunal brought charges against twenty-five individuals for Class A war crimes and 5,700 for Class B violations. Of these, 984 received death sentences (920 executed), 475 received life sentences, 2,944 received “some” prison time, 1,088 individuals obtained acquittals, and 279 charged individuals never went to trial.

Efforts to reduce non-capital sentences began almost immediately. In 1950, General Douglas MacArthur, serving as Supreme Allied Commander, Far East, ordered reduced sentences for good behavior and paroled those serving life sentences after fifteen years. In April 1952, Japanese citizens began to demand the release of prisoners because they had not received “fair trials” or because their families were suffering hardships. The Japanese (mostly civilians, by the time) began to argue that the war criminals were not criminals — they were only doing their duty. In May 1952, President Truman issued an executive order establishing a clemency and parole board for war criminals. By the end of 1958, the Tokyo Tribunal ordered all Japanese war criminals not already executed, including Class A convicts, to be released. All of these people were suddenly “rehabilitated.”

In Japan, there is a difference between legal and moral positions on war crimes. Japan violated no international law, they argue, because Japan did not acknowledge such international laws. But the Japanese government has “apologized” for such incidents because they caused unnecessary suffering. The Japanese like to apologize for issues where no apology is adequate. It’s all about “saving face” for themselves — without genuine guilt for the horrific suffering they inflicted upon men (and women) who were only doing their duty as members of the Allied forces.

The other side

The preceding discussion in no way attempts to absolve American servicemen who were also guilty of war crimes, particularly since this topic addresses war crimes perpetrated against Japanese soldiers taken as prisoners of war. There is no excuse for such behavior, even though there are reasons for it.

Recently landed Marines of the 1st Marine Division on the island of Guadalcanal were not in a particularly happy frame of mind on 11 August 1942. Since their arrival five days earlier, they had been under constant assault by Japanese naval artillery and air attacks. Ground fire and snipers continually harassed the Marines, and they were getting fed up with it.

The Marines weren’t too happy with the Navy, either. Two days earlier, Admiral Fletcher made the difficult decision to withdraw several amphibious supply ships that were in the process of unloading ammunition, food stores, and medical equipment needed to sustain the Marines in ground combat. Although the average Marine grunt didn’t realize it, Fletcher’s decision was prudent and responsible because, had Fletcher not withdrawn those supply ships, Japanese submarines and destroyers would have sunk them.

On 12 August, a Marine security patrol observed what they thought was a white flag near the Matanikau River, not too far from the Marine perimeter. Later in the day, Marines captured a Japanese sailor who, after a liberal dose of whiskey, divulged that many of his comrades in the jungle were starving and on the verge of surrendering.

At this point, Guadalcanal Marines were full of beans, itching for a fight, and still untested in combat. The information received that day was exciting but unverified. A drunken sailor is hardly a good source of information, and while everyone knew what a white flag meant, could it be possible that the Japanese were interested in surrendering this early in the game?

To find out, the Division Intelligence Officer (G-2) was tasked to lead a reconnaissance patrol to the area where an earlier patrol had spotted a white flag. On the evening of 12 August 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Goettge, USMC, the G-2, led a 25-man patrol to verify the veracity of earlier reports, accept the surrender of Japanese soldiers, disarm them, and escort them back to Marine lines. The patrol’s secondary mission was to gather information about the enemy.

The problem was that Marine operations had already scheduled a patrol. Since it wouldn’t do to have combat patrols bumping into one another in the dense jungle or after dusk, the Marines simply re-tasked the patrol and placed it under the operational control of Colonel Goettge.

Goettge hand-selected several men to accompany him on patrol. Lieutenant Commander Malcolm L. Pratt was a navy surgeon. Captain Wilfred Ringer, the 5th Marines intelligence officer; First Lieutenant Ralph Corey, a Japanese language specialist, and First Sergeant Stephen A. Custer, from the 5th Marines staff. The riflemen assigned to the patrol included Sergeant Charles C. “Monk” Amdt, Sergeant Frank L. Few, and Corporal Joe Spaulding.[3]

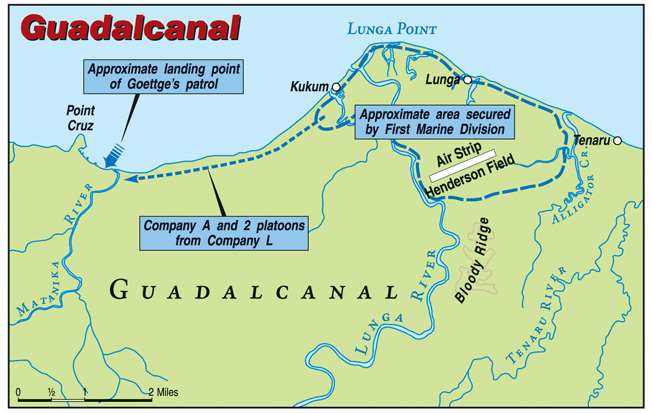

After loading his men into the Higgins boat, the patrol shoved off at 18:00 hours, a delay caused by Goettge making last-minute changes to the route of march. Rather than leading the patrol directly into the heavy jungle from the Marine perimeter, Goettge elected to ferry the patrol by boat to the west of Lunga Point, east of Point Cruz, and just off the mouth of the Matanikau River. It was already getting dark, so Goettge planned to land his men, bivouac for the night, and proceed up the Matanikau River in the morning.

In the darkness, Goettge lost sight of his landing point, and he directed the landing point further east. As the boat approached the mouth of the river, its engines throbbing loudly in the night, Japanese defenders became aware of their enemy’s presence. As the boat came into contact with the shoreline, the Marines disembarked on the west side of the river — precisely where they were warned not to go.

Once the Marines were ashore, Goettge had his Marines establish a defensive perimeter on the beach. With the Japanese sailor trussed in a tightrope, Goettge, Ringer, and Custer followed the prisoner into the jungle toward the supposed location of the weary, starving, ready-to-surrender soldiers. Shortly after these men disappeared into the thick foliage, gunfire shattered the night. Goettge and the Japanese sailor fell dead; Ringer carried the wounded Custer back to the beach within hail of small arms fire. Dr. Pratt tended to Pratt and a few other wounded men. Members of the patrol returned fire to keep the enemy from approaching their position.

After a few minutes, the Japanese stopped firing. Sergeant Few, Sergeant Arndt, and Corporal Spaulding low-crawled into the jungle to find Goettge and the Japanese squid. Goettge was found dead, with bullet wounds to his head. Spaulding crawled back to the beach to secure the help of additional men. While he was making his way, Japanese soldiers rushed Sgt Few’s positions. Few, thinking the Japanese were his men, called out with a challenge, but rather than offering a password, the Japanese soldier bayonetted Sergeant Few. Sergeant Few, now highly pissed off, grabbed the Japanese soldier’s rifle, took it away from him, bayonetted him to death, and shot and killed another soldier with his pistol.

As Few and Arndt returned to the beach, they killed two additional Japanese. Captain Ringer established a tight defensive perimeter but knew that his vastly out-numbered men could not sustain a major assault. Worse for the Marines, the Japanese knew exactly where they were. It was only a matter of time. Meanwhile, Dr. Pratt, wounded in an earlier fusillade while treating a wounded Marine, died from his wounds. Captain Ringer tried to improvise without a radio by firing tracer rounds into the air. The call for help went unanswered.

Next, Ringer asked for volunteers to return to the Marine perimeter. Sergeant Arndt, a trained scout and a strong swimmer, agreed to swim five miles back for help. Arndt departed at around 01:00 on 13 August. As Arndt waded into the surf, the remaining men accepted their situation in stride; they were, after all, Marines.

Slowly and carefully, Japanese soldiers approached the Marine position. The closer they got, the more accurate their rifle fire. Twenty Marines dwindled to ten. Custer had fallen to gunfire. An hour had passed since Arndt went into the water, and Ringer had no idea if he’d made it. He dispatched Spaulding on the same mission.

An hour later, the Marine’s situation turned desperate. Only four Marines remained effective, including Ringer, who led his men toward the jungle with hopes of concealing themselves. Within a few moments, only Sergeant Few remained alive. If the sergeant had any chance of survival, he had to leave the area immediately. He did not believe any of his comrades were still alive. While under enemy fire, Few headed for the surf. Upon reaching deeper water, Few observed the Japanese mutilating the dead Marines. “The Japs closed in and hacked up our people,” Sergeant Few testified. “I could see their swords flashing in the sun.”

At 08:00, an exhausted Sergeant Few dragged himself out of the water near Marine’s lines and delivered his report to a Marine officer. Within a short time, the 5th Marines commander ordered Company A, supported by two platoons from Company L and a machine gun section, to proceed to Point Cruz. The problem was that they were looking for the Goettge patrol where he was supposed to be. A thorough search of the area failed to locate the remains of the Marines — that was the official report. However, Private Donald Langer, one of the scouts, reported spotting dismembered body parts half buried in the sand. Before Marine headquarters could organize a third search party, a tropical storm hit the island, and the remains of the Marines were washed out to sea.

The final disposition of the remains of the Goettge patrol is unknown. What is not disputed is that the Japanese mutilation created far-reaching consequences. Accounts of what happened spread throughout the entire Pacific theater. The least of these consequences was that the 1st Marine Division lost its entire intelligence section in a futile, ill-conceived, poorly executed patrol. The worst of these consequences (arising from two provocative Japanese behaviors — perfidy and mutilation) was that the Marines began hating the Japs with unbridled passion. They subsequently refused to take prisoners, even those few who indicated surrender. And the Marines were angry at themselves for having fallen for such an obvious trap. They wouldn’t make that mistake again.

News of this incident reached the United States through Richard Tregaskis. No one in the United States thought that their armies should take prisoners. “The only good Jap is a dead Jap” became a popular catchphrase, and in the minds of Marines and soldiers alike, if the Japs wanted a dirty war, they’d get one. Private Langer recalled, “After this, ‘no prisoners’ became an unspoken agreement.” After the Goettge incident, the brutish killing of Japanese became as common as Pacific Island palm trees.

Conclusion

Two wrongs do not make a right — we all heard that from our parents. At the same time, on this issue, those who monitor battlefield behavior (as well as the folks back home) must understand that war is not a humane endeavor.

The military forces of all countries train their combatants to locate, close with, and kill the enemy. Armed conflict is, by its very nature, deadly. Combat is an adrenaline-rich environment, fluid, stressful, and always influenced by the actions (or perceived actions) of the opposing force. Combatants make life and death decisions within split seconds, and no combatant is ever dispassionate about what transpires within those mere seconds.

The enemy is not human. He is the enemy. He must surrender or die. The duty to inflict death or greater pain and suffering on the enemy is what we pay our soldiers to do, and they must do it with intentional resolve, in the space of a second, in a lethal environment. Once these events have begun, they cannot be turned on and off again as a faucet. No government bureaucrat or military lawyer has the right to judge these events when they’ve never experienced them firsthand.

Before and during the Pacific War, Japan’s imperial forces violated every tenet of generally accepted battlefield proscriptions. They murdered, mutilated, tortured, raped, and inflicted grossly inhumane treatment upon those who, as POWs, could no longer defend themselves. When American Marines and Soldiers became aware of these inhumane behaviors, they reacted as any civilized person would (or should). In this context, the Japanese obtained their just rewards at the hands of U. S. military personnel.

Sources:

- Bergerud, E. M. Touched with Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific. Penguin Books, 1997.

- Manchester, W. Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific. Little/Brown, 1980.

- Tregaskis, R. Guadalcanal Diary. Landmark Books, 1943; Modern Library, 2000.

- Wukovits, J. The Ill-Fated Goettge Patrol Incident in the Early Days of Guadalcanal. Warfare History Network (online), 2016.

Endnotes:

[1] Unit 731 under LtGen Shiro Ishii, was established under the direct order of Emperor Hirohito. POW victims suffered amputations without anesthesia, vivisection, transfusing horse blood, and biological weapons testing. Ishi was never prosecuted because the U.S. Government offered him immunity in exchange for handing over the results of his experiments. We may deplore General Ishi for his incredible inhumanity, but we must abhor the American government even more.

[2] Feigning injury or surrender to lure an enemy and then attacking or ambushing them.

[3] Sergeant Few was prominently mentioned in the book titled Guadalcanal Diary by Richard Tregaskis, who described him as a half-breed Indian “vastly respected by the men because he is, as the Marines say, ‘really rugged.’”

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Que?

LikeLike

“Flags of Our Fathers” author James Bradley says the Japanese twisted the bushido code to make it very brutal. Even so, it is exceedingly difficult to restrain our soldiers when abuses occur. The Japanese army in that time period was extremely brutal everywhere they went.

Tom

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read Brady’s book. Japanese Bushido was brutal from its beginning, from the early Edo period (1600s), but with much earlier “ruthless” roots. Thanks for stopping by, Tom.

LikeLike

I loved this report, Sir. Superb data and reporting of history.

LikeLike